A youthful employee here at the store here recently asked me what comics and creators I liked. Among the creators I mentioned were Will Eisner and Harvey Kurtzman, whereupon I was asked “What did they do?”

After I picked my jaw up off the floor, I pointed out they were famous, not for having the two major comic awards, the Eisner and Harvey’s, named after them, but what they did to deserve the honor.

Will Eisner (March 6, 1917–January 3, 2005) entered comics in 1936, and by the time Superman appeared on the newsstands he was an old hand; not just writing, penciling and inking, but editing and packaging material. Comics had been mostly reprinted newspaper comic strips up till then, but old material was being snapped up by the growing market. With Jerry Iger, Eisner realized new material would be needed to fill the books, so they set up a shop system to supply stories and art.

Will Eisner (March 6, 1917–January 3, 2005) entered comics in 1936, and by the time Superman appeared on the newsstands he was an old hand; not just writing, penciling and inking, but editing and packaging material. Comics had been mostly reprinted newspaper comic strips up till then, but old material was being snapped up by the growing market. With Jerry Iger, Eisner realized new material would be needed to fill the books, so they set up a shop system to supply stories and art.

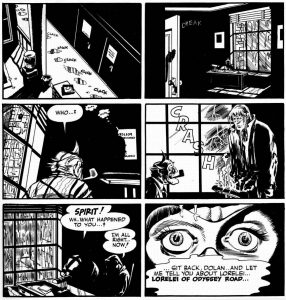

As the popularity of comic books grew, a newspaper syndicate approached Eisner about creating a 16-page weekly booklet to be put in Sunday newspapers. He jumped at the chance because newspapers catered to an older audience, which would allow him to expand the subject matter of his stories. The strip needed a hero, but the syndicate insisted on a costumed hero, so he compromised by giving his hero a mask and gloves, and the Spirit was born.

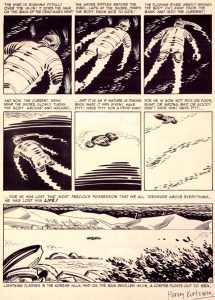

The eight (and later seven) page stories ran the range in themes from humor through crime and Noir, sometimes starring the Spirit front and center, other times featuring him as just an observer, sometimes without him ever knowing what really happened. But far beyond Eisner’s writing skill was his ability to use visual narrative in telling his stories. While newspaper strip artists like Milt Caniff, Chester Gould, Roy Crane and others could do wonderful things with visuals, they were limited to three to four panels a day (a few more on Sunday), and had to feature some repetition, however cleverly managed, to keep the reader up to date day after day. Eisner had the freedom to do complete story sequences. His use of panel-to-panel continuity, “camera” angles, and depth of field made his narrative incredibly readable, and never just as gimmicks.

The eight (and later seven) page stories ran the range in themes from humor through crime and Noir, sometimes starring the Spirit front and center, other times featuring him as just an observer, sometimes without him ever knowing what really happened. But far beyond Eisner’s writing skill was his ability to use visual narrative in telling his stories. While newspaper strip artists like Milt Caniff, Chester Gould, Roy Crane and others could do wonderful things with visuals, they were limited to three to four panels a day (a few more on Sunday), and had to feature some repetition, however cleverly managed, to keep the reader up to date day after day. Eisner had the freedom to do complete story sequences. His use of panel-to-panel continuity, “camera” angles, and depth of field made his narrative incredibly readable, and never just as gimmicks.

Eisner worked on the Spirit for a couple years before he was drafted into the army during World War Two. The comic section was continued by various hands with occasional input from him, until his return from service. His work from 1946-1950 is considered the highlight of the Spirit by most. But having conquered the sequential story, he began to apply his narrative skills to instructional projects for businesses, the army and others.

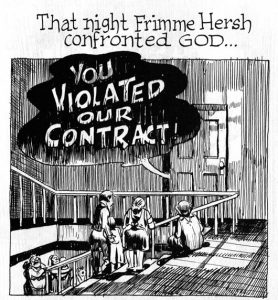

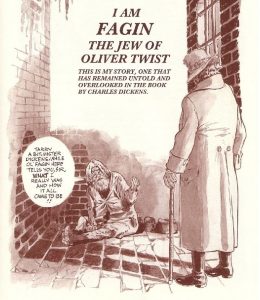

In the late 1960s and 70s he became fascinated by the emergence of underground comics. It was not so much the subject matter, but that artists had broken away from standard genre restrictions to do more personal work. And the books were surviving without using the old-boy network of distribution. This eventual lead him to write and draw the book A Contract with God. Certainly not the first “graphic novel”, and not even a novel. But it was probably the greatest influence on American cartoonists bringing attention to, and expanding the artform. He’s explored subjects including his own tenement childhood, and Jewish life, as in Fagin the Jew, a look at what life would have been like for Dickens’ character. All of this is the reason one of the major awards in cartooning was named after him.

In the late 1960s and 70s he became fascinated by the emergence of underground comics. It was not so much the subject matter, but that artists had broken away from standard genre restrictions to do more personal work. And the books were surviving without using the old-boy network of distribution. This eventual lead him to write and draw the book A Contract with God. Certainly not the first “graphic novel”, and not even a novel. But it was probably the greatest influence on American cartoonists bringing attention to, and expanding the artform. He’s explored subjects including his own tenement childhood, and Jewish life, as in Fagin the Jew, a look at what life would have been like for Dickens’ character. All of this is the reason one of the major awards in cartooning was named after him.

(To read Eisner you can check out any of his late works, though most are between printings. While the complete Spirit stories were republished in 26 archives, and DC did two books of reprints, I’d recommend finding the two Harvey Publications comics issues published in the sixties. If you can accept lesser condition they can be found at reasonable price. The stories were picked by Eisner himself, and were some of his best.)

Harvey Kurtzman (October 3, 1924-February 21, 1993) entered comics about ten years after Eisner, doing mostly humorous fillers and short pieces. It was when he began working at EC Comics that he began to bloom. Mostly writing his own scripts, he created some nice science-fiction stories before being handed the new Two-Fisted Tales. Originally planned to deal with a wide range of historical tales, Kurtzan slowly started to zero in on war stories, particularly the then-current Korean conflict. A second book was added to Kurtzman’s stable, Frontline Combat.

While not really anti-war, Kurtzman did believe in de-glamorizing war in his stories, parting ways from most other books on the newsstands which usually featured healthy Anglo-Americans easily beating hordes of drooling enemies, often rescuing scantily clad women from their clutches. Kurtzman looked at the soldiers as human, good and bad, on both sides. It was later found that the FBI investigated these comics as possibly un-American, though nothing came of it

Kurtzman was also fascinated by the mechanics of war: submarine warfare, tanks, plane spotting and more. He was a stickler for details, at one point calling the Korean embassy to find out how a house would be built there, and sending an assistant down in a submarine to get the sound of the klaxon horn right. But this love of detail slowed his production, so that he could not keep up with editor Al Feldstein’s pace on the horror and crime books. To give him a third, easier title to edit, EC gave him MAD.

Kurtzman started by doing take-offs on the types of stories that EC and other companies were putting out, but some swung into satires of current comics (Superduperman, Batboy and Rubin, Woman Wonder) as well as current comic strips, movies and even culture. As he had done on his war comics, he not only wrote each story, but did layouts for his group of regular artists to follow. Some chafed at this, but admitted his view was usually best. A comparison between the same artist’s work on the second EC humor book, Panic, will show this. Mad quickly became the bestselling EC magazine, spawning a legion of imitators.

Kurtzman started by doing take-offs on the types of stories that EC and other companies were putting out, but some swung into satires of current comics (Superduperman, Batboy and Rubin, Woman Wonder) as well as current comic strips, movies and even culture. As he had done on his war comics, he not only wrote each story, but did layouts for his group of regular artists to follow. Some chafed at this, but admitted his view was usually best. A comparison between the same artist’s work on the second EC humor book, Panic, will show this. Mad quickly became the bestselling EC magazine, spawning a legion of imitators.

When the negative publicity against comic books in the mid-50s crippled the industry, it was decided, with the 24th issue, to turn Mad into a magazine. Kurtzman, wanting more control over the magazine, left to create Trump magazine (no relation) for Hugh Hefner and his young Playboy empire. Unfortunately, Kurtzman could not rein in his perfectionism to keep to schedule, and Hefner pulled the plug after two beautiful issues. Kurtzman went on to do features for a number of national magazines, finally starting a low-budget effort for Jim Warren (publisher of Creepy et al) Help magazine, which featured early work by future underground luminaries like Gilbert Shelton, Jay Lynch and Robert Crumb, as well as assistant editors Terry Gilliam (Monty Python) and Gloria Steinem (MS Magazine). There were the classic Goodman Beaver strips with Will Elder, and “fumettis”: comic stories using photographs, including stars and future stars like Tom Posten, Jean Shepherd, Woody Allen and John Cleese (as a man having an affair with his daughter’s “Barbee” doll). The magazine struggled through twenty some issues before failing.

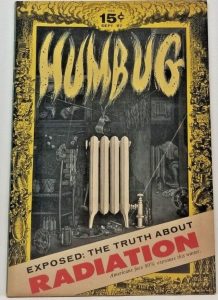

With several artists contributing the financing, they started Humbug magazine without any real plan for it. There was some nice work in it, but it didn’t fit any regular slot on the newsstand and failed. Meanwhile Kurtzman and Will Elder had started the strip Little Annie Fanny for Playboy magazine. Well paying, but Hefner, a frustrated cartoonist, oversaw every side of the comic strip, which Kurtzman chafed at.

Meanwhile the underground comix revolution was growing, with many artists acknowledging their debt to EC comics, and especially Kurtzman. They considered him the father of underground comix, he allowed himself as maybe the father-in-law.

Meanwhile the underground comix revolution was growing, with many artists acknowledging their debt to EC comics, and especially Kurtzman. They considered him the father of underground comix, he allowed himself as maybe the father-in-law.

Ill-health finally forced him away from work and eventually took his life. But he left an influential legacy which led to naming the other notable award in comic, the Harvey.

His work in Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat is available in nice tpb reprints. Trump and Humbug were both reprinted in HC. MAD is around in hardcovers, and Kurtzman’s run was reprinted in eight magazines, Tales Calculated to Drive You Mad. The first seven volumes of the old Mad paperbacks featured Kurtzman’s work, and reading copies can be found.